What do ‘great’ teachers do?

November 2022

Many of us will either have seen, experienced or delivered what we think is a fantastic lesson – possibly even all three – but what makes it so good? Maybe it depends on your perspective. Does it feel and look the same for teacher, observer and pupil, and if not why not?

The problem is that it simply isn’t possible to measure the quality of teaching easily. I think we’d probably all agree that great teaching should result in pupils learning but learning, like teaching, is also highly complex, multifaceted and difficult to measure. This is because there are many, often hugely different, outcomes or metrics that could be used to assess teaching effectiveness and learning e.g. pupil test scores from attainment data; measures of pupil enjoyment and feedback from pupils about the quality of the teaching they’ve experienced.

Sometimes, some metrics take precedence over others. For example, in many countries, schools and institutions are measured, graded and ranked according to pupil outcomes. Pupil attainment and progress are good examples of metrics that are often used as proxies to determine teaching effectiveness. The problem lies when accountability metrics such as these are used to determine ‘rewards’ e.g. gaining an Ofsted ‘outstanding’; performance related pay or gaining a promotion. Where this is the case, systems can be, have been and will be gamed . For an example of this, please see the report here by Schools Week (2018) on the now defunct European Computer Driving Licence qualification.

Goodhart’s Law: “When a measure becomes a target it ceases to be a good measure.”

(Strathern, M., 1997, p. 308)

Bearing this in mind, it’s important then to recognise that each measure of teaching quality or teacher effectiveness, has its own limitations. Take for example data obtained about the effectiveness of teaching from the act of observing a lesson. An observer may presume that the intended audience for this lesson will be the pupils, however, it could well be that the intended audience for the lesson, from the perspective of the teacher, is both the children and the observer. As the observer could be in a position of authority e.g. a line manager or senior leader, the teacher being observed may well be interpreting or anticipating what the observer considers to be good practice and as a result, changes their behaviour to match the perceived observer’s expectation, which can happen subconsciously. This could be considered to be an example of the ‘demand effect’, and may result in a false impression about what happens in that teacher’s lessons on a day-to-day basis. This is only one example of how teacher observation data can lead to inaccurate conclusions, there are many others.

What does the research tell us?

People have been asking what makes teaching effective for a long time. Research conducted in the 1970s on this very topic, has recently found its way back into schools in the form of Barak Rosenshine’s Ten Principles of Instruction.

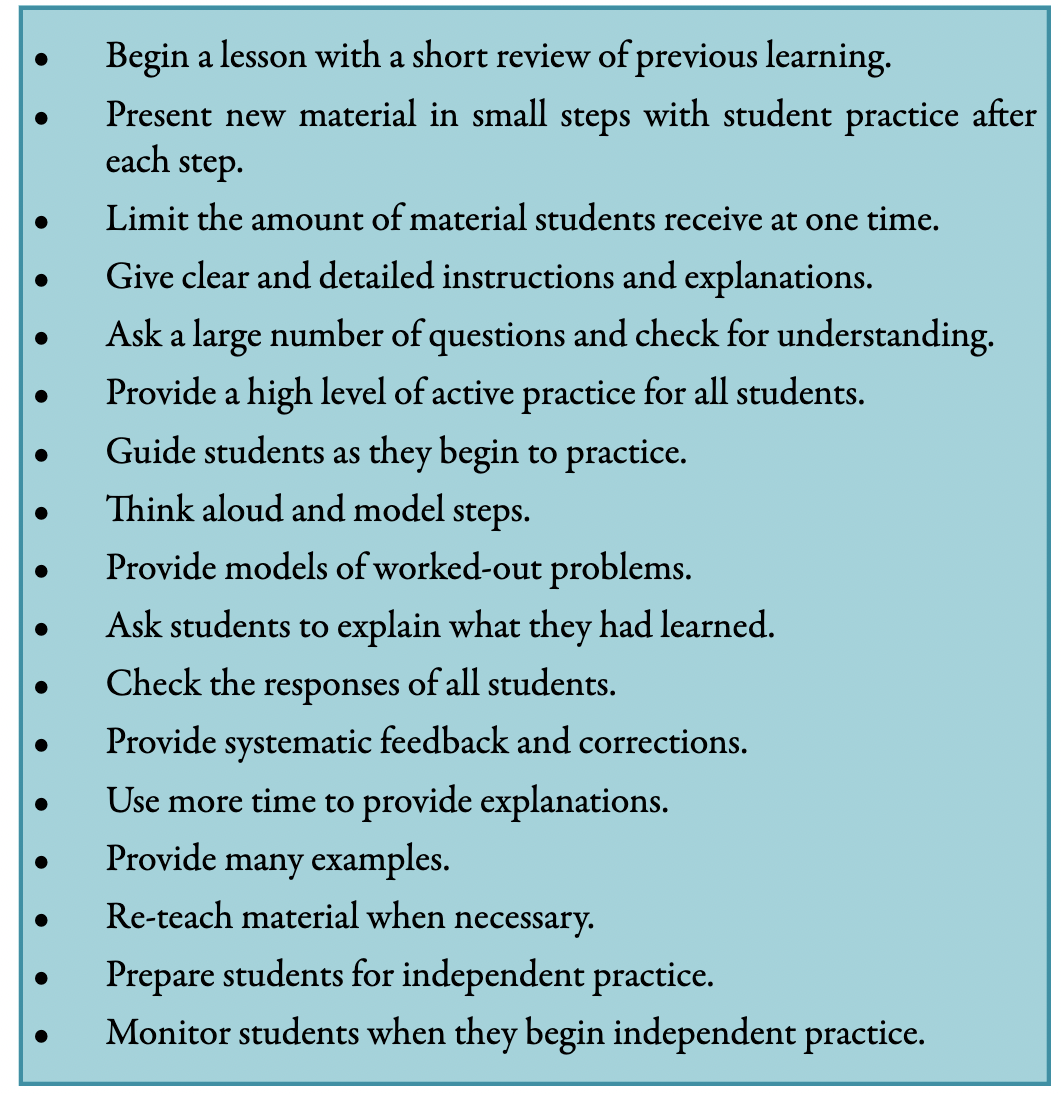

Barak Rosenshine, formally a Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Illinois, linked ‘great’ teaching to improving the quality of learning in school and therefore increased gains in student achievement. Drawing on findings and research from cognitive science e.g. what’s known about memory; learning strategies that help students to complete complex tasks and and the observed practices of ‘’master teachers’’*, he produced his “ten research-based principles of instruction”, which he later expanded to 17 instructional procedures to the right here:

Alongside these “instructional procedures” sit teacher behaviours. Rosenshine and Professor Norma Furst, identified the top five characteristics or variables of teacher behaviour associated with effective teaching as: teacher clarity, enthusiasm, task oriented and/or businesslike behaviour, variability of approach, and student opportunities to learn.’

Since the 1970s, thousands of studies have been conducted to try and determine an answer to the title of this Insight. For example, take a look at the report “What makes great teaching?” published by The Sutton Trust back in 2014. However, when looking at evidence it’s really important to recognize that not all studies are equal! A knowledge of the methodology and statistical analyses performed in each study is essential in order to (a) evaluate the ‘soundness’ of the conclusions drawn and (b) think critically about the generalizability and applicability of these findings to other classroom settings.

*defined as “those teachers whose classrooms made the highest gains on achievement tests.

(Taken from: Rosenshine, B. (2010). Principles of Instruction (No. 21). International Academy of Education.)

Can we make all teachers ‘great’?

Everyone has room for improvement. People have the capacity to get better at what they do and this includes teachers. Providing opportunities for vicarious learning through observing others, developing mastery and receiving meaningful feedback are all essential for powerful and efficacious teacher development.

One way of providing a space for practice in order to gain confidence, develop mastery and engage positively with feedback, is by using scenario-based learning. TSP has a range of tools teachers, schools and training providers can use to do exactly this. Please see what we have to offer on our product page and contact us to discuss how we can support you.

References

- Koretz, D. (2017). The Testing Charade. University of Chicago Press.

- Strathern, M. (1997). “Improving ratings”: audit in the British University system. European Review , 5(3), 305–321.

- Rosenthal R. and Rosnow R.L. (2009). A Re-issue of Artifact in Behavioral Research, Experimenter Effects in Behavioral Research and the Volunteer Subject. Oxford University Press.

- Rosenshine, B. V. (1978). Academic Engaged Time, Content Covered, and Direct Instruction. The Journal of Educational Research, 160(3), 38–66

- Rosenshine, B. (2010). Principles of Instruction (No. 21). International Academy of Education. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000190652

- Rosenshine, B. and Furst, N. (1971). Research on Teacher Performance Criteria. In B. O. Smith (Ed.), Research in teacher education: a symposium. (pp. 37–72). Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy : the exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman.